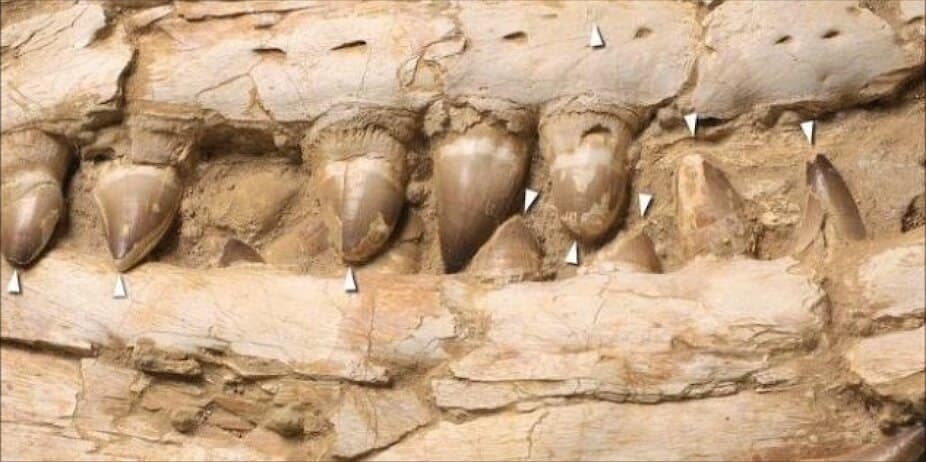

Thalassotitan teeth. Credit: Nicholas Longrich

Introduction

In the ancient depths of our planet's oceans, a formidable creature reigned supreme. Over 66 million years ago, alongside the last of the dinosaurs, mosasaurs, colossal marine lizards, dominated the seas. These formidable reptiles, resembling a fusion of Komodo dragons and sharks, could reach lengths of up to 12 meters. Remarkably diverse, they evolved numerous species, each carving out a unique ecological niche. Some fed on fish and squid, while others devoured shellfish and ammonites.

A Groundbreaking Discovery

Now, a groundbreaking discovery has shed light on a new chapter of mosasaur history—one that reveals their appetite for not just any prey, but for their own kind.

Thalassotitan Atrox: The Formidable Predator

Unearthed in the Oulad Abdoun Basin of Khouribga Province, just an hour outside Casablanca in Morocco, lies the remains of a previously unknown species of mosasaur. Named Thalassotitan Atrox, this formidable predator hunted down large marine animals, including other mosasaurs.

Anatomy and Adaptations

While most mosasaurs possessed elongated jaws and small teeth suited for capturing fish, Thalassotitan boasted a distinctly different anatomy. Its short, wide snout and powerful, killer whale-like jaws were built for a different purpose. The broad skull facilitated the attachment of massive jaw muscles, equipping it with a devastating bite. Such adaptations indicate that this mosasaur was specialized in attacking and tearing apart large prey.

Evidence of Carnivorous Feeding

Notably, its conical teeth bear a striking resemblance to those of orcas, exhibiting signs of chipping, breakage, and extensive wear. These tooth damages, absent in mosasaurs that fed on fish, suggest that Thalassotitan likely engaged in bone-crunching encounters with marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs, sea turtles, and even other mosasaurs.

Fossilized Remains: Clues to Predatory Behavior

Remarkably, at the very same site, paleontologists discovered what appears to be fossilized remains of Thalassotitan's victims. The rocks surrounding the Thalassotitan skulls and skeletons are replete with partially digested bones from mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. These bones, including those from the half-meter skull of a long-necked plesiosaur, display evidence of partial acid erosion. This intriguing observation implies that these animals were killed, consumed, and subsequently regurgitated by a large predator. Although conclusive proof that Thalassotitan was the perpetrator remains elusive, it stands as the primary suspect, as no other creature fits the profile of the predator in question.

Insights into Ancient Ecosystems

Thalassotitan's position atop the marine food chain offers valuable insights into ancient ecosystems that thrived just before the cataclysmic asteroid impact 66 million years ago, which marked the demise of the dinosaurs.

A Diverse Predatory Era

Thalassotitan's coexistence with a dozen other mosasaur species off the coast of Morocco underscores the remarkable diversity of predators during this era. This diversity suggests that the lower levels of the food chain were equally rich, supporting an abundance of life in the oceans. The flourishing presence of mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, giant sea turtles, ammonites, a myriad of fish species, mollusks, sea urchins, and crustaceans alludes to the robustness of the marine ecosystem, which was not in decline prior to the asteroid impact.

The Cataclysmic Asteroid Impact

Contrary to gradual environmental changes as a precursor to extinction, the sudden annihilation of mosasaurs and other marine creatures resulted from an unforeseen catastrophe—the colossal Chicxulub asteroid strike. The impact launched immense quantities of dust and soot into the atmosphere, effectively blocking out sunlight. Thus, the end of mosasaurs and their contemporaries arrived swiftly and unpredictably, akin to a lightning strike from a clear blue sky.

The Origin and Evolution of Thalassotitan

Interestingly, the evolution of mosasaurs, including Thalassotitan, may have originated from a previous catastrophic event. Intriguing parallels can be drawn between the evolution of these giant carnivorous marine reptiles and that of their terrestrial counterparts, the Tyrannosauridae. Both groups began diversifying and growing larger around 90 million years ago, during the Turonian stage of the Cretaceous period. This period coincided with significant extinctions on land and in the seas approximately 94 million years ago, caused by extreme global warming and a "supergreenhouse" climate fueled by volcanic CO2 emissions. The aftermath of these extinctions witnessed the disappearance of giant predatory plesiosaurs from the oceans and the eradication of massive allosaurid predators on land. As a result, mosasaurs and tyrannosaurs seized the opportunity to claim the apex predator niche. Thus, the evolution of Thalassotitan and T. rex itself owed its existence to a prior mass extinction event.

The Fragility of Top Predators

The tale of top predators such as Thalassotitan holds a captivating allure, as their colossal size and position at the pinnacle of the food chain both fascinate and make them inherently vulnerable. As one ascends the food chain, the number of predators diminishes. It takes countless small fish to sustain a large fish, numerous big fish to satiate a small mosasaur, and a multitude of small mosasaurs to fuel a single giant mosasaur. This rarity among top predators coupled with their insatiable appetite renders them highly susceptible to disruptions in the food supply.

The Cycle of Extinction and Evolution

Indeed, the sensitivity of these predators to environmental changes serves as a catalyst for their study in the context of extinction. The Thalassotitan's existence exemplifies the precarious nature of being a top predator. While evolution drives the development of increasingly larger predators over short timescales, the specialization required for the apex predator role heightens vulnerability to catastrophes over long timescales. Consequently, mass extinctions wipe out the top predators, and the cycle of evolution commences anew.